The Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s (JPL) internal network had uninvited guests for ten months who, among other things, had access to data from current space missions such as the Mars mission - as well as manned missions. JPL is a research facility that works for the US’s space agency NASA, among others. It is unclear who was behind the attack. However, speculation points in the direction of an APT group. The successful intrusion into the network and the reading of data are a direct result of sloppiness and procrastination on the part of those responsible.

Destructive decision

The official investigation report on the incident (PDF; link opens in a new window) paints a devastating picture. Among other things, JPL is “unable to monitor assets in its own network”. In addition, the security measures taken were either incomplete or inadequate. For example, there was no network segmentation that would have made it more difficult for the attack to penetrate and spread. Security flaws were not fixed for months or even years. Furthermore, there are shortcomings in the distribution of responsibilities as well. For example, the inadequately trained administrators did not know whether and how to process reports of suspicious activities. Overall, JPL's security policies and practices differ from those of the rest of the higher authority - NASA. NASA has its own Security Operations Center (SOC), which is staffed around the clock. JPL also has its own SOC, but it is not available around the clock. JPL is obliged to report certain incidents, but there was no check as to whether JPL actually acted in compliance with this requirement.

“Coordination difficulties” ultimately led to a delay in the resolution of the incident.

No finest hour

So NASA/JPL have certainly not covered themselves in glory in recent years, at least in the area of IT security. Example: If a security measure is not implemented within six months, a special waiver is required. This must be signed by a total of four senior figures (including the CISO). Once issued, however, there is no “expiry date” for these waivers. A total of 153 of these special waivers were still open in October 2018. In more than one third (54) of the cases, the employee who requested the release was no longer working for JPL. In 13 cases, the waiver requests were up to 11 years old.

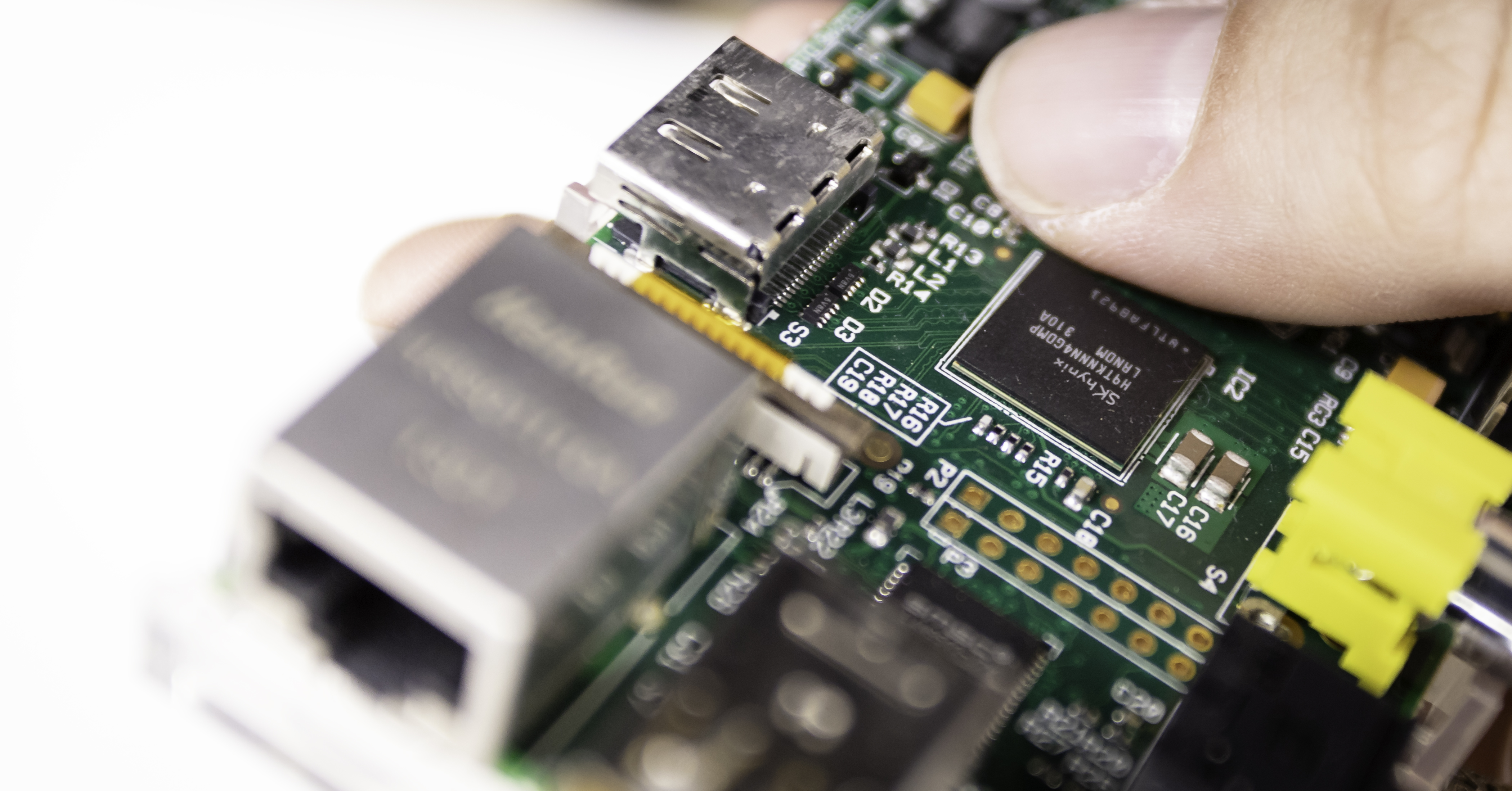

With all these failures, it is not surprising that the attacker(s) could take their sweet time to look around the network completely undisturbed. A Raspberry Pi - a cigarette-box-sized single-board computer worth about $40 - became a stepping stone into the entire network. Neither the SOC nor the local authorities were aware of this device’s presence, which should have been registered in a database.

Shadow IT: not just a NASA problem

NASA and JPL are in good company with this problem. Many other companies find themselves in the same situation - flat network structures without segmentation, legacy equipment that cannot be replaced by current equipment, unclear responsibilities and a lack of emergency planning, coupled with administrative chaos. Such an environment is an open invitation for intruders of all kinds, because not only is operational data managed there (whether it’s data from a Mars mission or bids for an important tender), but also data on customers, business partners, suppliers and service providers. In the worst case scenario, the compromised network becomes the starting point for forays to other networks.

In the past, there have also been cases from the business world in which an attacker had hidden a minicomputer in the business premises. For an extended period of time the devices posed as the company's WLAN hotspot, attempting to snarfle company data. There are plenty of hiding places - behind copiers, under desks, in cable trays or cable ducts.

There are further parallels between NASA and many medium-sized companies. This is where hardware is used that sometimes dates back to the 80s and 90s. What NASA uses as hardware for the Voyager mission is perhaps a production machine in a small company whose control software is no longer compatible with current operating systems. These devices and machines should actually be isolated from the rest of the network. In reality, however, they are often not, either out of convenience or ignorance.

It is not at all a matter of preventing incidents at any cost.

As the NASA report admits: intrusions into the network are unavoidable in the long term. However, it is up to those responsible to take the right steps to uncover and counteract them.

Both JPL and numerous small and medium-sized enterprises still have a long way to go here.

Picture credits

Header image: NASA Mission Control during mission STS 128; National Aeronautics and Space Administration's public domain material