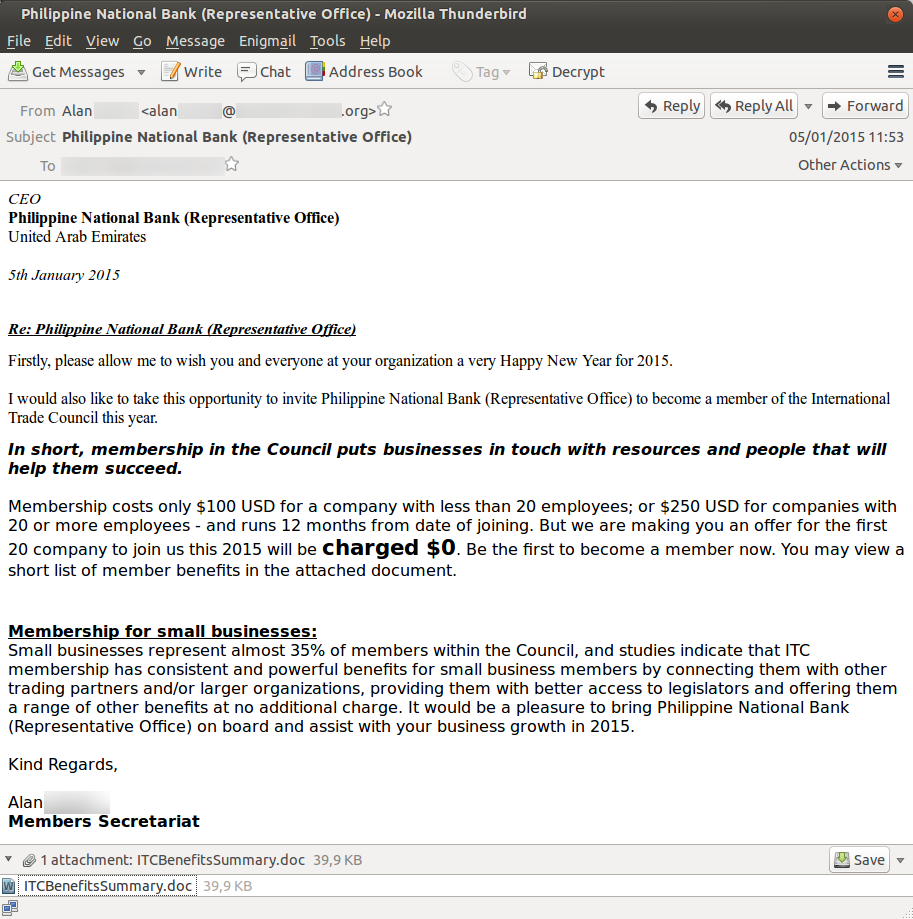

Infection Vector

The attacker(s) sent a specially crafted email to at least one employee of the attacked enterprise. The email’s body reveals a business-related topic: an offer to become member of this year’s International Trade Council. Nevertheless, the offer is directed at the Philippine National Bank, not the enterprise actually receiving the email. This could be a trick to make the recipient even more curious to look at the attached document, because he/she received documents not issued for him/her.

The G DATA experts alerted the aeCERT about the incident and their analysis results.

In this case, the attachment is a Microsoft Word document which tries to exploit the vulnerability described in CVE-2012-0158 in order to drop and execute malware dubbed “Kraken HTTP”.

The G DATA security solutions detect the malicious document (08E834B6D4123F0AEA27D042FCEAF992) as Exploit.CVE-2012-0158.AH and G DATA’s proactive Exploit Protection technology also prevents the attack before the PC can be infected.

The Malware, advertised on the Underground Market

“Kraken HTTP” is sold on at least one underground market as a commercial product. Someone, who claims not to be the author of the malware, promoted the malware with a kind of banner which has quite a visual impact. Have a look at the “ad” that was published back in December 2014.

The banner describes the botnet:

- its technical features

- the available commands (classic ones, such as visiting a website using the infected bot, download and execute a command or a library, update and uninstall)

- the plugins one can use: file stealer, ad-clicker, form grabber, …

The command “visiting a website” using the infected bot could be used by the attackers as an entry point for blackmailing the infected user. The attackers could visit websites that are regarded as illegal in the respective country and could then ask for ransom and threaten to release information about the alleged violation to any seemingly official entity who would then investigate against the victim.

The flyer also reveals the price of the malware: The basic binary costs $320 and each plugin must be paid for separately, for example $50 for the file stealer, $60 for the ad-clicker and up to $350 for a configurable form grabber. Accepted payment methods are the usual virtual currencies and pre-paid options.

A price list found on a different website, also posted in December 2014, lists the binary’s price as $270 and some additional modules, such as a “Edit Hosts module” ($15), a “Botkill module” ($30) and a “Bitcoin monitor module”($20).

Furthermore, “Kraken HTTP” is advertised as “a new, revolutionary botnet […] and very noob-friendly”. Noob is a word describing “that someone is new to a game, concept, or idea; implying a lack of experience.” But now let’s have a look at what the botnet really is.

Marketing vs. Reality

After having a glimpse at the ad designed to promote the malware, we analyzed a sample of it: 3917107778F928A6F65DB34553D5082A, which is detected as Gen:Variant.Zusy.118945. We decided to analyze some features mentioned in the flyer and on the other website to evaluate their power and implementation.

Feature: “Bypass UAC”

As expected, the malware does not really bypass the UAC. It rather uses a classic trick already used by several malware instances. It uses a legitimate Microsoft binary in order to execute itself with administrator permissions. We already presented this technique in our

G DATA SecurityBlog article about the Beta Bot.

Feature: “Anti-VM”

The flyer explains that the botnet won’t work in a virtual machine. To detect whether the malware is running in a virtual machine, the malware author checks if the following directories and the one file exist:

- C:\Program Files\VMWare\VMware Tools\

- C:\Program Files (x86)\VMware\WMware Tools\

- C:\WINDOWS\system32\VBoxtray.exe

Furthermore, the malware checks if following applications analysts usually use are being executed:

- Wireshark: a network analyzer

- Fiddler: a web proxy used to debug HTTP flow.

We can see the tools detection:

The folders & bot files simply have the “hidden” attribute set in Microsoft Windows. If you configure you system to show hidden files and directories, you can perfectly see them:

Feature: “Process & registry persistence”

The malware persistence uses a registry key in order to be executed automatically in case the system is rebooted. The key is HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\Windows:

The malware repeatedly checks whether this entry is removed. In case the entry is removed, the malware will create a new one. However, instead of removing it, we can simple rename the path to the executable in order to switch off the persistence mechanism.

So, the malware does not have any clever persistence features either.

Feature: “Path & variable encrypted”

We identified two kinds of “encrypted” data:

- Some paths are encoded using base64 algorithm, such as: JVdJTkRJUiUA (%WINDIR%) and JWFwcGRhdGElaa== (%appdata%)

- Some data is encrypted (RC4), such as the C&C information:

Feature: “Bitcoin monitor plugin”

The Bitcoin monitor plugin is even more amusing. It is not advertised on the flyer but on the other website we found. The malware monitors the infected user’s clipboard. If the user copies a Bitcoin address to the clipboard, it will be replaced by an address pre-configured by the botmaster. A Bitcoin address is an identifier of 26-35 alphanumeric characters which represent the owner of a Bitcoin wallet, for example something like 3J98t1WpEZ73CNmQviecrnyiWrnqRhWNLy.

We can easily imagine that the plugin’s “test” is prone to produce false positives, because any alphanumeric text copied by the user will be automatically changed without reason if it has a length between 26 and 35 characters. Ok, we admit that the German word “Kraftfahrzeughaftpflichtversicherung” (36) would not be harmed when copied, but what about “Bundesausbildungsfoerderungsgesetz” (34) or “radioimmunoelectrophoresis” (27)? Just kidding. But any string, from strong passwords to bank account numbers and more could be affected.

Feature: “Download & Execute”, the next Step

This feature allows installing further malware on the affected PC in case the attackers decide the current machine is interesting enough. “Kraken HTTP” is only the first stage in this attack and can be seen as reconnaissance tool.

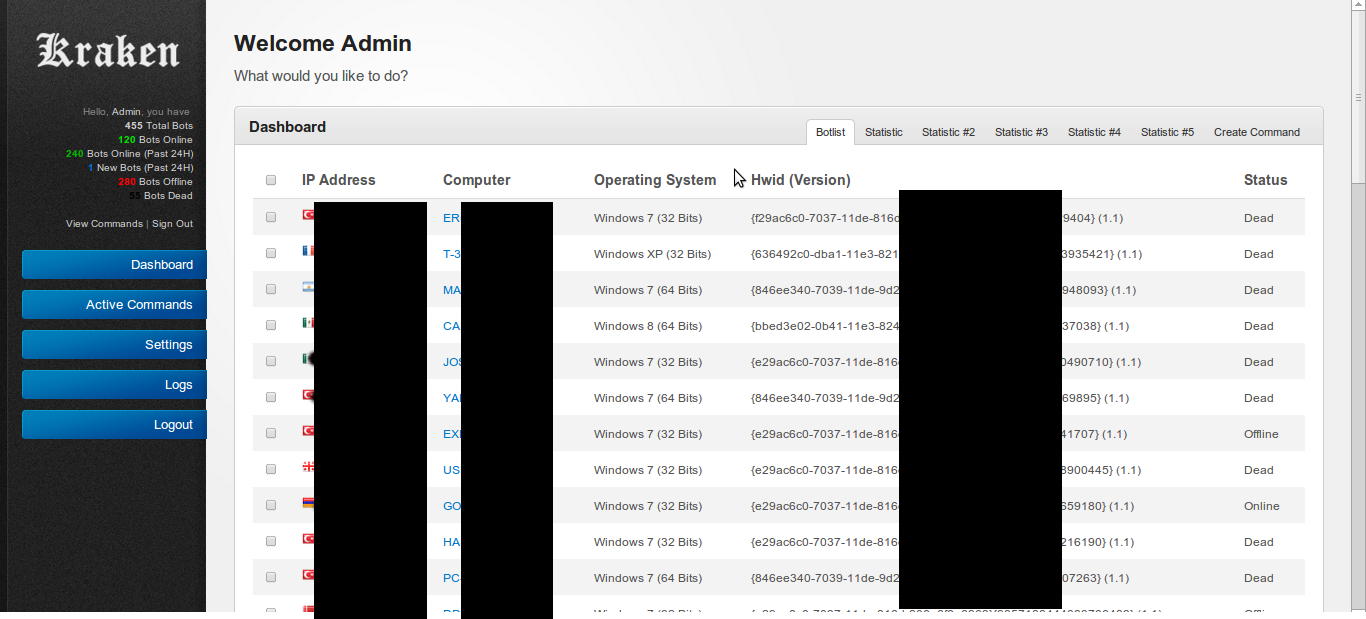

Administration Panel

The experts of the G DATA SecurityLabs had access to the panel used by “Kraken HTTP” but the source code is protected by a commercial packer called IonCube loader. Nevertheless, we can reveal some screenshots of the administration panel which are available on the underground. Note that some of the texts contain mistakes:

Conclusion

We suppose that the Kraken botnet was developed by a beginner. The malware does not include advanced malware technologies and no groundbreaking innovations, even though those were advertised. Many sensitive strings are not encrypted, such as installation paths, anti-virus listings, insults against the analysts and much more.

To sell the botnet malware, the author used a quite sexy marketing flyer, but, actually, the malware turned out to be rather simple.

“Kraken HTTP” was said to be used during an espionage campaign against the energy sector, especially against targets in the UAE. We have now identified a specific target from this geographical region and have obtained one of the spear phishing emails used. Even though the targets that are known by now are rather high-level targets, the malware code as well as its features is not advanced.

We are surprised to see this piece of code has been used carrying out targeted attacks rather than broader criminal activities. It is not surprising that attackers use vulnerabilities that are older, because, unfortunately, many computers are likely to be still out of date and so the attack works. Despite the fact that the vulnerability used is not a new one, the malware does not have the common features that we saw during other targeted attack campaigns. Compared to incidents like Uroburos, the Kraken malware is not good enough to “catch the big fish” if we want to stick with to the metaphor. So, from the current point of view, there are three theories:

- The attackers who developed the Kraken malware might have chosen to diversify their business and chose to attack special interest targets themselves.

- The attackers identified infected machines in the business sector and followed the tracks to see what else they might be able to get from the companies.

- The actual espionage team voluntary chose to use a kind of usual and rather simply botnet malware in order to distract analysts from seeing a deeper meaning behind this attack and make them disregard it as ‘daily cybercrime business’.